Endorsed by the Council of the American Association of Geographers: October 18, 1998; updated April 5, 2005; revised November 1, 2009; and revised March 15, 2021.

I. Preamble

Geography is a field of study that examines the relations among people, places, and the more-than-human world. Geographical scholarship ranges from quantitative analysis to humanistic research undertaken in many different social and environmental contexts. Thus, in our research, teaching, and professional life, geographers are confronted with a wide variety of ethical considerations, each requiring careful reflection and thoughtful action.

This Statement on Professional Ethics outlines core principles to inform the ethical conduct of members of the American Association of Geographers (AAG) and the geographical community more broadly. These principles provide general guidelines applicable to geographers working in diverse professional settings. AAG members, in particular, are urged to familiarize themselves with, reflect on, and act in accordance with these principles when working in a professional capacity. Members of the AAG are required to abide by AAG’s Professional Conduct Policy and Procedures, and many geographers must also conform to ethical requirements related to research with human subjects as interpreted and enforced by institutions and funders. Geographers also belong to multiple professional communities, each with its own ethical standards. This Statement should therefore be viewed in conjunction with these other codes, statements, and standards.

This Statement is written with the intent to encourage active, thoughtful engagement with ethical issues in relation to the various circumstances that geographers encounter in their professional lives. These principles address general circumstances, priorities, and relationships, and should therefore be seen as starting points for consideration of the ethical issues attendant to our activities as professional geographers. Each of us must be ready and willing to make, and be equipped to defend, ethical choices that also go beyond the principles laid out here.

II. Do No Harm

An overarching ethical principle, serving as the basis for all academic and professional activities of geographers, is that we should do no harm. Our activities inevitably affect the people and places we study, societies, ecosystems, biodiversity, climate and landforms, our students, and those who help make our work possible. It is imperative that both prior to and during the performance of our professional work – ranging across human geography, physical geography, nature-society geography, and GIScience – each geographer should think through the possible ways that our activities might cause harm. Harms include those affecting the dignity, livelihood, and well-being of human and non-human lives as well as the resilience and sustainability of ecosystems and environments. Beyond direct harms, we should also consider long-term and indirect implications, and possible unintended consequences, being willing to step back from or terminate those activities when harm feels unavoidable. The obligation to do no harm should supersede other goals of seeking or communicating new knowledge.

In making assessments of potential harm, geographers must be sensitive to the unequal power relationships surrounding our activities. We frequently occupy powerful positions relative to our research participants, and it is all too easy for us to be unaware of, or to forget, the impact that these power imbalances can have on those affected by geographical research. Our activities and reflections require special care when the subject matter involves Indigenous peoples, racialized or ethnic minorities, and other vulnerable groups, including when research is conducted with and by members of those groups. Potential issues include physical and social threat and danger to participants both from outside and within such communities, violation of their intellectual property, and threats to the viability of a group and its territory. These can stem not only from published data, but also from the data collection process itself. Information thus should not be extracted from such communities without their consent. Benefits to the community must be recognized as such by the community, and it is particularly important for researchers to consider whether they are accepting funds from sources whose agendas are seen as inimical to such communities.

Geographers’ activities and reflections about potential harm also require that we take special care when engaging with non-human individuals, groups, species, and ecosystems. Where methods and activities may be invasive or potentially cause long-term alterations to environments, strong justification and appropriate safeguards are reasonable obligations. In such situations, the costs and benefits of the research should be weighed carefully in advance, not just once the work is underway, and be continually reassessed throughout the research process.

Actions that pose serious risks to the dignity and well-being of participants or other affected parties fall outside the boundaries of accepted geographical scholarship and have no place within the academic study and professional practice of geography. Geographical scholarship depends upon the right to academic freedom, but academic freedom cannot justify violating the well-being of human and non-human lives. It thus follows that geographers should eschew collaborating with or seeking funding from public or private organizations known to participate in warfare or similar acts of violence – such as those associated with the military, intelligence, security, or police – without adequate ethical safeguards, since such participation can create risks for both researchers and the researched. When such collaboration is deemed ethical, geographers are responsible for prominently and publicly reporting such relationships.

III. Respect People, Places, and the More-Than-Human World

Geographers should respect people, places, and the more-than-human world in all aspects of our work as professional geographers. Respect for well-being underlies the principle of doing no harm, actively affirming the responsibility of geographers to use our work to enhance the well-being of others, especially for those who are most vulnerable to harm. The principle of respect acknowledges that all geographical knowledge is situated and should depend on building relationships informed by an ethics of care for the well-being of both human and non-human lives as well as the places and environments they call home. Geographers should therefore make reasonable efforts to treat those with whom we interact with dignity and respect, conducting ourselves with honesty and integrity when engaging in academic and professional activities.

An important sign of respect and care in geographical scholarship involving human subjects is conducting research with, rather than on, participants and avoiding exploitative or extractive research. Geographers must be accountable not only to our own professional communities but to all of the relations involved in the production and dissemination of geographical knowledge. Geographers should also carefully reflect upon how we represent ourselves, research participants, and places in our research, teaching, and professional life. Respectful geographical scholarship is based upon an appreciation for reciprocity with research participants in the co-production of geographical knowledge. Reciprocal relationships are built through active listening and an obligation to share the benefits of geographical research with those it directly affects.

The principle of respect also extends to the treatment of non-human individuals, groups, species, and ecosystems affected by geographical research. Geographers have an ethical obligation to develop geographical knowledge that aims to alleviate the harms caused by anthropogenic environmental change. Geographers should seek to enhance the well-being of more-than-human lives and the environmental conditions conducive to their survival and capacity to thrive. In circumstances where the well-being of one living entity negatively impacts the well-being of another, geographical researchers should carefully consider how our own interventions may affect the well-being and survival of all parties before deciding whether or how to intervene.

IV. Maintain Ethical Professional Relationships

Geographers must engage with colleagues, research associates, students, and staff in a respectful manner. This includes respect for the rights of others, a refusal to spread gossip, a commitment to discussing differences openly and honestly, and attention to the power asymmetries in which we are all embedded. Geographers must not plagiarize, fabricate or falsify evidence, or knowingly misrepresent information. Representations of others’ work should be devoid of prejudice or malice, notwithstanding differences of interpretation, personality, ideology, theory, or methodology. We should take time to reflect before posting online, avoiding cyberbullying and flame wars. However, raising ethical concerns about the conduct of others does not, in itself, constitute cyberbullying if there are reasonable grounds for such concerns and they are presented in a professional manner.

The scope of collaboration, rights and responsibilities of those participating, co-authorship, credit, and acknowledgment should be openly and fairly established at the outset. We must be particularly attentive to actual or perceived conflicts of interest, exercising care to protect the interests and well-being of the less powerful.

Geographers should strive to create and maintain a diverse, pluralistic, and inclusive professional community. It is our moral responsibility to respect the dignity of all, valuing a diversity of intellectual commitments and respecting individual differences. In particular, we should continually work to empower the voices and views of underrepresented communities. Diversity should also be central to teaching and advising. Instructors should strive to create a classroom environment that fosters respect for and engagement across different learning styles, interpretations, and theoretically informed perspectives, in ways that empower underrepresented positionalities and identities and create safe learning spaces. Instructors should take student perspectives that differ from or critique their own views as seriously as they are presented, bearing in mind the principles of respect and doing no harm, modeling for others the value of respectful disagreement and debate. Teaching assistants should be treated with respect, as full partners in delivering a course: instructors should actively mentor their development as teachers, provide clear instructions about expectations, timely feedback on their performance, and ensure that their workload does not exceed contractual obligations. Advisors should be attentive to students’ overall well-being, including mental health, standing ready to provide personal support and facilitate access to professional counseling when appropriate and allowable.

V. Do Not Discriminate or Harass

Geographers must not discriminate, harass, bully, or engage in other forms of professional misconduct as defined by the AAG Professional Conduct Policy and Procedures. AAG members should familiarize themselves with their obligations as set out in this document, including procedures for acting on and reporting harassment.

In evaluating the professional performance of peers and other employees, geographers should not discriminate against individuals or groups using criteria irrelevant to professional performance. Such irrelevant criteria generally include (but are not limited to) age, class, ethnicity, gender, marital status, nationality, politics, physical disability, race, religion, and/or sexual orientation.

In addition, geographers should adhere to fair employment practices. They should not discriminate against individuals or groups using criteria irrelevant to the positions for which they are hiring. Geographers are encouraged to strive for inclusivity, justice, and equity in all employment practices.

VI. Obtain Informed Consent for Research, Manage Data Responsibly, and Make Results Accessible

Geographers working with human communities must obtain free, prior, and informed consent of research participants. The consent process should be a part of project design and continue through implementation as an ongoing dialogue and negotiation with research participants. Minimally, informed consent includes sharing with potential participants the research goals, methods, direct and indirect funding sources or sponsors, expected outcomes, anticipated impacts of the research, and the rights and responsibilities of research participants. It must also establish expectations regarding anonymity and credit. Researchers must present to research participants the possible impacts of participation, and make clear that despite their best efforts, confidentiality may be compromised, or outcomes may differ from those anticipated.

Geographers whose research involves humans, based in countries where there is an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or similar process, must obtain institutional approval and follow its stipulations about informed consent, modification of research practices, reporting of adverse events, etc. Geographers should also familiarize themselves with relevant documents on which such consent is based; in the US, this is particularly informed by the Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. At the same time, geographers should be aware that considerations of ethics go beyond and may in some circumstances differ from such rules.

The informed consent process is necessarily dynamic, continuous, and reflexive. When research changes in ways that may directly affect participants, geographers must revisit and renegotiate consent. The principle of doing no harm means that the right to refuse research goes beyond specific individuals approached through the IRB process, and also includes the right of communities to refuse participation. Informed consent does not necessarily imply or require a particular written or signed form. It is the quality of the consent, not its format, which is relevant.

Whenever appropriate, results of research should be shared with research participants, local colleagues, host agencies, and affected persons and communities in a format that is accessible to them. Whenever possible, acknowledgement, including authorship, should be determined in a fair and transparent manner.

In general, geographers should make data and findings publicly available to the greatest extent allowable by funding agencies and by our ethical principles, and in a fashion that is consistent with the goal of doing no harm to the people, places, and environments we study. Thus, in some situations, generalization or other measures such as the use of pseudonyms will be necessary to protect privacy, confidentiality, and limit exposure to risks. Most funding agencies have guidelines for the use and distribution of data and research findings and may require a data use agreement as a condition for grant or contract awards. Such an agreement may include provisions designed to protect de-identified data from re-identification, and conditions relating to data storage, protection, publication, and transmission. Geographers should carefully document how datasets are collected, constructed, and managed, and carefully guard against any data breaches, while promptly notifying affected individuals or communities if a breach does occur. Geographers should reflect carefully on the potential problems that so-called “big data” pose with respect to data management, de- and re-identification, and privacy.

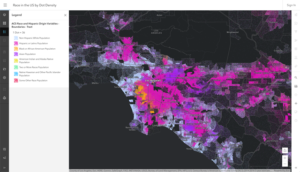

Geospatial technologies introduce further challenges with respect to potential violations of privacy and confidentiality of individuals and groups. In using these technologies, researchers should make reasonable efforts to protect the health, well-being, and privacy of research participants. Understandings, expectations, and preferences regarding privacy differ across and within societies. Further, privacy depends on the nature of the data, the context in which they were created and extracted, and the expectations and norms of those who are affected. Particular efforts should be made to guard against any breaches, especially when such data could be used to undermine the interests of communities or community members, and when specific agreements have been made to keep such data out of the public domain.

The following examples of research approaches involving geospatial technologies are particularly likely to raise issues of privacy and confidentiality, and therefore should be undertaken with special care: (1) automated tracking of the locations and movements of individuals or vehicles; (2) the use of images from satellites, aircraft, UAVs (drones), or ground-based sensors that are of sufficient resolution to identify individuals or vehicles; (3) the use of high resolution geographic location to link data in ways that violate personal confidentiality; and (4) any use of big data that compromises privacy, confidentiality, or violates other ethical principles in this Statement, even when such data is considered publicly available. The use of geospatial technologies and other geographical techniques within the context of warfare, or to support other acts of violence, is inconsistent with principles of doing no harm and securing free, prior, and informed consent, and is therefore outside the boundaries of ethical geographical research and practice.

VII. Disclose Funding Sources, Affiliations, and Partnerships

Geographers should reject funding from any sponsor that compromises the principles of ethical research. The conditions under which data can be used, and restrictions on the use of data after the end of a research project, should be clarified prior to accepting funds. Ethical quandaries are particularly likely to be encountered when seeking funding from military, intelligence, security, and policing agencies as well as private corporations to support research or to undertake government- or corporate-sponsored projects. Geographers should be open and candid, avoiding undertaking any task that requires us to compromise our professional and ethical responsibilities.

All funding sources, affiliations, sponsorships, and partnerships should be fully disclosed in a comprehensible manner at the time that informed consent is requested from research participants, because prospective participants have the right to assess this information as they consider giving or withholding consent. Where relevant, geographers should undertake due diligence to trace and disclose not just intermediary but also original funding sources. Transparency and disclosure also mean reporting in a timely fashion any changes in funding sources, affiliations, or partnerships to affected individuals or communities during the course of research.

Disclosure and transparency must be practiced throughout the research process, from the first stages through to the dissemination of research results in journals and other publications. Such transparency in the disclosure of funding source reporting, affiliations, and partnerships also applies to presentations of geographical research at AAG and AAG-affiliated meetings as well as in other scholarly and professional forums. Both during the research process and in any related publications and presentations, geographers should make explicit the extent to which governments, corporations, or other funding entities have limited or restricted research efforts.

In addition to disclosure, geographers should bear in mind that there may be other ethical implications involved in accepting funding and sponsorships. Geographers should carefully consider with due diligence the ethical integrity of those sources as well as conditions or expectations implied by any particular funding, sponsorship, affiliation, or partnership, and be ready to defend our decisions on ethical grounds. Similarly, ethical judgements about funding sources may extend beyond research to teaching, such as teaching in specific programs that are externally supported. Individual geographers should encourage their departments or other units to evaluate, reflect upon, and engage in thoughtful debate regarding the ethical implications of accepting such funding support, particularly in relation to the principle of doing no harm.

VIII. Weigh Competing Ethical Obligations

Ethics are not based on absolute moral standards but are situational. This means taking into account the particular context of an act. In this spirit, geographers must weigh competing ethical obligations to research participants, students, professional colleagues, employers, and funders, among others, while recognizing that obligations to research participants are usually primary. These varying relationships may create conflicting, competing, or crosscutting ethical obligations, reflecting both the relative vulnerabilities of different individuals, communities, or populations, asymmetries of power implicit in these scholarly relationships, and the differing ethical frameworks of collaborators representing other disciplines or areas of practice. These considerations may also include geographers’ own safety, especially if they are a member of a marginalized group, or in cases where research participants, funders, or sponsors are in a position of power over the researcher.

Geographers must often make difficult decisions among competing ethical obligations while recognizing our obligation to do no harm. We remain individually responsible for making thoughtful and defensible ethical decisions. If geographers’ ethical responsibilities conflict with law, regulations, or other governing authority, we should clarify the nature of the conflict and take reasonable steps to resolve the conflict consistent with the principles of ethics laid out in this Statement on Professional Ethics.

We are about 3 weeks away from the Annual Meeting! The completely virtual 2021 Annual Meeting, April 7-11, will feature 800+ paper sessions and panels on a wide range of topics as well as 27 poster sessions. Browse the

We are about 3 weeks away from the Annual Meeting! The completely virtual 2021 Annual Meeting, April 7-11, will feature 800+ paper sessions and panels on a wide range of topics as well as 27 poster sessions. Browse the

The most recent issue of the Annals of the AAG has been published online (

The most recent issue of the Annals of the AAG has been published online ( In addition to the most recently published journal, read the latest issue of the other AAG journals online:

In addition to the most recently published journal, read the latest issue of the other AAG journals online:

The 2023 Special Issue of the Annals invites new and emerging geographic scholarship situated at the crossroads of Race, Nature, and the Environment. In seeking contributions from across the discipline, we welcome submissions that advance critical geographic thinking about race and the environment from diverse perspectives and locations; that utilize a broad array of geographic data, theories, and methods; and that cultivate geographic insights that cut across time, place, and space. Abstracts of no more than 250 words should be submitted by e-mail to

The 2023 Special Issue of the Annals invites new and emerging geographic scholarship situated at the crossroads of Race, Nature, and the Environment. In seeking contributions from across the discipline, we welcome submissions that advance critical geographic thinking about race and the environment from diverse perspectives and locations; that utilize a broad array of geographic data, theories, and methods; and that cultivate geographic insights that cut across time, place, and space. Abstracts of no more than 250 words should be submitted by e-mail to

The AAG is pleased to announce the recipients of the three 2020 AAG Book Awards: the John Brinckerhoff Jackson Prize, the AAG Globe Book Award for Public Understanding of Geography, and the AAG Meridian Book Award for Outstanding Scholarly Work in Geography. The AAG Book Awards mark distinguished and outstanding works published by geography authors during the previous year, 2020. The AAG will confer these awards at a future event to be determined, once the travel and in-person meeting restrictions have been lifted.

The AAG is pleased to announce the recipients of the three 2020 AAG Book Awards: the John Brinckerhoff Jackson Prize, the AAG Globe Book Award for Public Understanding of Geography, and the AAG Meridian Book Award for Outstanding Scholarly Work in Geography. The AAG Book Awards mark distinguished and outstanding works published by geography authors during the previous year, 2020. The AAG will confer these awards at a future event to be determined, once the travel and in-person meeting restrictions have been lifted.

Two virtual events are upcoming that may be of interest to AAG members:

Two virtual events are upcoming that may be of interest to AAG members: The William T. Pecora Award is presented annually to individuals or teams using satellite or aerial remote sensing that make outstanding contributions toward understanding the Earth (land, oceans and air), educating the next generation of scientists, informing decision makers or supporting natural or human-induced disaster response. Sponsored jointly by the Department of the Interior (DOI) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and established in 1974, the award honors the memory of Dr. William T. Pecora, former Director of the U.S. Geological Survey and Under Secretary, Department of the Interior, whose early vision and support helped establish the Landsat satellite program. Nominations for the 2021 awards must be received by the Award Committee by May 14, 2021.

The William T. Pecora Award is presented annually to individuals or teams using satellite or aerial remote sensing that make outstanding contributions toward understanding the Earth (land, oceans and air), educating the next generation of scientists, informing decision makers or supporting natural or human-induced disaster response. Sponsored jointly by the Department of the Interior (DOI) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and established in 1974, the award honors the memory of Dr. William T. Pecora, former Director of the U.S. Geological Survey and Under Secretary, Department of the Interior, whose early vision and support helped establish the Landsat satellite program. Nominations for the 2021 awards must be received by the Award Committee by May 14, 2021.

“You Baby.” It’s Saturday morning. Jeffrey, who is chronologically well out of his early teenage years, but very much still there in spirit, is awake and calling to me with his favorite insult. He’s mostly non-verbal, but this particular phrase is one that he articulates well enough for anyone to understand.

“You Baby.” It’s Saturday morning. Jeffrey, who is chronologically well out of his early teenage years, but very much still there in spirit, is awake and calling to me with his favorite insult. He’s mostly non-verbal, but this particular phrase is one that he articulates well enough for anyone to understand.

Adam Mandelman, The Place with No Edge: An Intimate History of People, Technology, and the Mississippi River Delta (LSU Press, 2020)

Adam Mandelman, The Place with No Edge: An Intimate History of People, Technology, and the Mississippi River Delta (LSU Press, 2020)