Illinois Agriculture

It’s no secret, especially to its residents, that Illinois is a divided state. There’s Chicago, and then there’s not Chicago. However, Illinois’ rural farming region should not be overlooked when it comes to appreciating and understanding what makes this state tick. While calling oneself a farmer is as simple as being able to annually produce and sell more than $1,000 of agricultural goods (something my wife’s never-ending herb garden could likely do in most years), the number of farms in and around Chicagoland has increased. Since 2002, Illinois has lost just over 2,000 farms, yet the number of farms in the Chicago Metropolitan Statistical Area has increased, due in large part to the addition of smaller farms, less than 200 acres in size, that cater to the region’s ever-increasing demand for local, fresh food (more on urban agriculture in an upcoming Newsletter piece).

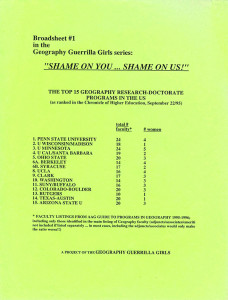

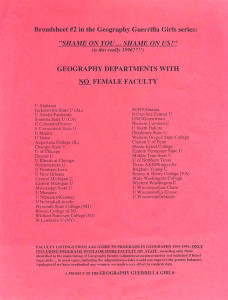

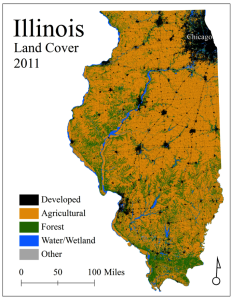

According to the U.S. Geological Survey’s 2011 National Land Cover Dataset, 70 percent of Illinois’ land cover was classified as either cultivated cropland or pasture/hay (FIGURE 1). The state ranks 7th in the U.S. in total agricultural sales ($17.2 billion), but ranks 3rd when considering only the sale of crops such as corn and soybeans, which in 2012 covered over 95 percent of Illinois’ cropland. Illinois farmers produce between 15 and 20 percent of the U.S. total combined corn/soy crop annually (FIGURE 2). East-central Illinois was the country’s first major cash-grain farming region. Known as the Grand Prairie, this region, prior to Euro-American settlement, was a large grassland/wetland/oak savannah ecosystem. Because of its lack of relief it was poorly drained and largely ignored – except for cattle barons who used the untillable land as pasture – as the state was being settled in the 1800s. As decades passed, and as drainage ditches were dug and clay field tile were installed, the productive capacity of this region’s fertile soil was eventually realized. As these large parcels of pasture were tilled, and because individual landowners could not farm it all themselves, it necessitated the beginning of the now ubiquitous system of renting privately-owned cropland to others; a system by which landowners are paid a per-acre sum by a tenant who maintains the owner’s land. In Illinois, and across much of the rest of the Corn Belt, well over 50 percent of all farmland in most counties is rented.

Most farms in Illinois have grown over the years. Of the state’s 75,000 farms, nearly 8,000 (~10 percent) are 1,000 acres or larger. However, those 8,000 farms maintain over half of all of the state’s farmland. The idea that these big, “corporate” farms are industrializing the agricultural landscape is yarn easily spun to the uninformed, but one that is blatantly incorrect. In 2012 Illinois had 3,716 corporate farms. This seems impressive, especially when the prototypical “family farm” continues to disappear, but 90 percent of these so-called “corporate” farms were, in fact, what the U.S. Department of Agriculture refers to as “family corporations” (FIGURE 3). In other words, they were still family farms. The land was not owned by Cargill, Monsanto, or any of the other large, multinational corporations often blamed for the demise of farming (although such corporations do have considerable influence in modern U.S. agribusiness), but for tax purposes the family had decided to create a business. In reality, only 0.5 percent of Illinois farms are non-family, corporately-owned entities. These non-family, corporate-owned farms work an equally small percentage of the state’s total agricultural land – 0.7 percent. The Illinois “corporate” agricultural landscape mirrors exactly that of the entire United States: 0.5 percent of farms, 0.7 percent of farmland…numbers that have changed little over the past four decades.

Chicago’s importance in U.S. agricultural production and processing, by and large, has waned over the past half-century. Once the center of our country’s beef (and to a lesser extent pork) processing industry, Chicago, save for a handful of specialty uses for corn-based products (e.g. high fructose corn syrup), sees little of what is produced in much of the rest of the state. If not used locally to produce biofuels or to feed Illinois’ dwindling numbers of livestock (Illinois accounts for only 1.2 percent and 6.6 percent of U.S. cattle and hog sales, respectively), most corn and soybeans are brought from the fields in which they grew to one of the many hundreds of giant, glistening grain elevators that can be found along Illinois’ railroad lines – many of which head south to out-of-state processing facilities or to ports along the Mississippi River where they will continue south for export out of the Gulf of Mexico (FIGURE 4).

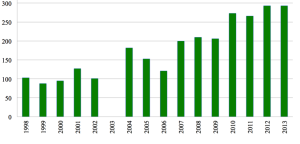

Geographer William J. Doolittle said, “Agriculture may well be the most comprehensive of geographical topics. It involves modification of both the biological and physical components of the environment, and it incorporates social and economic components with distinctive spatial manifestations” (Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 82, pp. 386-401). Agriculture and rural areas will be the focus of a number of sessions at the upcoming Chicago meeting. Indeed, many have already begun to take advantage of these topics’ increasing breadth and depth by reporting on – at AAG Annual Meetings – the myriad issues related to our rural and agricultural landscapes (FIGURE 5). We hope you will join us!

— Chris Laingen

Eastern Illinois University