The New England Town: Not a Village

Photo and permission by Betty Austin.

The New England town and its town meeting form of government invoke images of roadside town line signs and real democracy playing out on the floor of a wood stove heated frame town house in a small town somewhere in Boston’s hinterlands (fig.1). The New England town is a municipality that encompasses an expanse of land and usually includes compact settlements (villages /hamlets) and rural areas. These political units evolved from the seventeenth century needs of people transplanting themselves from England to the shores of Massachusetts Bay. Demands of church and civic governance resulted in a blending of religious and town government affairs in early Massachusetts. John Winthrop, first governor of the Massachusetts Bay settlements that would develop in and around the Boston locale was a principal player in both Congregationalism and establishing the underpinnings of New England town formation and administration (Rudman 1965). Towns were charged with providing local services: laying out roads and maintaining them, education, police and fire protection, overseeing the poor, passage of ordinances to protect public health and promote the general welfare of the population. These municipalities were also authorized to raise taxes to support their functions. New England colonies established policies that encouraged contiguous settlement as the frontier advanced. This provided for better safety from both external and internal dangers. Indians and foreign powers presented threats from time to time. On the domestic front church and community leaders wanted to watch over their people to ensure no citizen strayed from social norms. Hester Prynne with her scarlet letter and the banishing of Roger Williams from Massachusetts are examples of the latter (Hawthorne 1850; Barry 2012). As time passed villages within the towns became the visual icon of much of the region (Wood 1997). However, even with villages, some quite large, the town continued to be the government (Murphy 1964). If growth or political pressure resulted in city status the city line conformed to the pre-existing town line. Colonies and later states made provisions for town lines to change as development and population patterns evolved. In some situations towns reverted to unorganized townships if loss of population dictated.

Towns in New England range in geographic area from a few hundred acers in the case of some island communities and compact urban areas to a more typical size of six miles by six miles or thirty-six square miles. This larger size represents the approximate service area of a colonial church or seat of town government. Most traffic was by foot or animal. Topography and barriers to travel were often considered in laying out town lines. Towns were created from unincorporated land by colonial and later state governments. As land came under private ownership and underwent settlement, towns were incorporated upon petition of the owners and residents. In some situations plantations (planting a settlement) were formed by the colonial or state government. Plantations have fewer home rule powers then towns and are an intermediate step to becoming a town. The official name of the State of Rhode Island is Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Our smallest state has the longest name. With population growth most plantations eventually became towns. Maine still has a few dozen of them. Many towns skipped ever being a plantation. Maine plantations have the powers of towns except they cannot enact land use ordinances without permission of the state. Most of New England is divided into towns. Larger places and some mid-sized municipalities have become cities. Cities have more complex governments than towns and this varies among states. Nearly half of Maine (most of its north and northwest) is comprised of surveyed but unincorporated townships. All have either small populations or no people.

Source: Waterville (ME) Morning Sentinel.

Towns that arose in the six New England states were governed by the open town meeting where a legislative body comprised of all voting citizens of the town gathered at annual or special meetings to transact the legal affairs of the town. Many small and mid-sized towns continue to conduct their business through open town meetings with each citizen representing himself/herself on the floor. Larger towns and cities have councils or town meetings made up of representatives elected from the general population. Selectmen, usually three or five, are elected by the voters and serve as the executive branch of the town. They are charged with carrying out the wishes of the majority of people voting at town meetings (Zimmermann, 1999; Bryan, 2004). These open meetings are at the forefront of the region’s political image. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 “Four Freedoms” speech (freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want and freedom from fear) was followed in 1943 by Norman Rockwell’s image of a citizen speaking at a classic open Vermont town meeting (Guptill 1946). That “Freedom of Speech” setting is often repeated in New England open town meetings today (Fig.2). Historically annual town meetings were held in March or April, after the hard part of winter and before planting season, a good window for farmers. As local governance became more complicated some towns moved their annual meetings to summer in order to better coordinate fiscal years with other property tax supported enterprises, such as consolidated school districts. In Maine school budgets are often voted on in June near the end of their fiscal year.

Open town meetings can be traced to the ancient Greek forum and provide an environment for citizens to vent, legislate and solve community problems. Debates involve roads, local welfare for the poor, schools, fire and police protection, etc. Each warrant article is acted upon and all citizens with voting power can participate. My six decades of attending open town meetings has resulted in a patchwork of memories encompassing thousands of discussions ,some friendly, others not. The amount of money involved may not have much to do with how heated an argument becomes. Sometimes $50 to repair the cemetery fence will generate more anger and stress than buying a $150,000 snowplow.

Photo by author

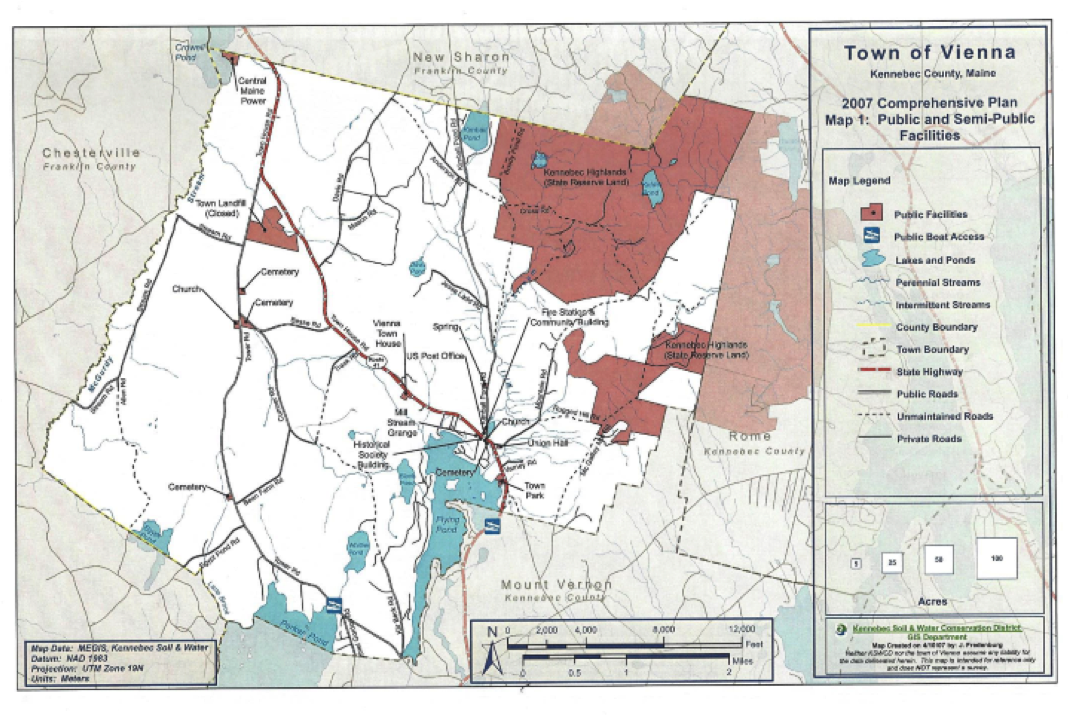

During the first decades of New England settlement town and religious meeting were often held in the same building, the meeting house. In the early stages of a town’s planting both kinds of gatherings were sometimes held in private homes or barns. With the passage of time and the growing demands of both church and town a separate structure, a town house, would be constructed to provide a place for town meetings and storage of government records. The raising of money to construct a town house represented a significant step in a town’s progress. Sometimes a wealthy citizen would donate funds for building the town house. This occurred in Vienna, Maine in 1854-55 when Joseph Whitter, a successful Boston merchant and child of Vienna, provided funds for a small Italianate style town house that continues to host town meeting (Fig.3). The structure is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (Vienna 2008). Vienna Town House is near the town’s geographic center on Town House Road and not at the village, ¾ of a mile to the southeast (fig.4).

Source: Vienna (Maine) Comprehensive Plan Committee. 2008. Town of Vienna Comprehensive Plan.

Vienna, ME: Plan Committee.

As the frontier swept west the New England town meeting was left behind. Settlers from the Mid-Atlantic and Southern regions defended strong county government and it prevailed as new land came under organizer local rule. Counties are weak in New England where most small towns and rural places are controlled by town administration. The one aspect of the New England town that did go west is the 36 square mile township that we recognize on land surveyed under the United States Northwest Ordinance of 1785.

This year’s AAG meeting in Boston is during traditional town meeting season. If you can find an open format one to attend consider making the effort. Small towns in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont are the best bet. Its real democracy in action and it will demonstrate to all that a New England town is not a village.

Paul B. Frederic is Professor of Geography Emeritus at University of Maine-Farmington and past Director of the Maine Land Use Regulation Commission. Email: frederic [at] myfairpoint [dot] net. He is in his eleventh year as a selectman in the Town of Starks, Maine. His research is on rural issues.

References

Barry, J. 2012. Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul. New York: Viking Press.

Bryan F. W. 2004. Real Democracy: The New England Town Meeting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Guptill A. 1946. Norman Rockwell: Illustrator. New York: Watson Guptill Publishers.

Hawthorne, N. 1850. The Scarlet Letter. Boston: Ticker and Fields.

Murphy, R. E. 1964. “Town Structure and Urban Concepts in New England” The Professional Geographer, Vol.16 (1): 1-6. DOI: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1964.001

Rutman, D.B. 1965. Winthrop’s Boston: A Portrait of a Puritan Town, 1630-1649. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Vienna (Maine) Comprehensive Plan Committee. 2008. Town of Vienna Comprehensive Plan.Vienna, ME: Plan Committee.

Wood, J.S. 1997. The New England Village. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Zimmerman, J. F. 1999. The New England Town Meeting. Westport, CT: Praeger Press.