The “Nation’s Report Card” on Geography Reveals a World of Opportunities

Periodically since 1994, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) has released its “report card” on geography education in America, providing a snapshot of student achievement. The most recent assessment was conducted in 2018 with a nationally representative sample of nearly 13,000 8th grade students.

NAEP assesses geography achievement in three content domains:

- Space and place questions measure students’ knowledge related to particular places on Earth, spatial patterns observed on Earth’s surface, and the physical and human processes that shape spatial patterns.

- Environment and society questions measure students’ knowledge of how people depend upon, adapt to, are affected by, and modify their natural environment.

- Spatial dynamics and connections questions measure students’ ability to understand geography as it relates to spatial variations and the connections among people and places.

Within each content domain, questions test student cognition in three dimensions: knowing (what is it? where is it?); understanding (why is it there? how did it get there? what is its significance?); and applying (how can geographic knowledge and understanding solve problems?).

When the 2018 NAEP geography report was released on April 23, among the things we learned include:

- There has been no change in the 8th-grade geography average score since 1994, which means three out of four 8th graders still perform below “NAEP Proficient” (defined as competency over challenging subject matter);

- There was a three-point decline in the geography average score since 2014;

- 2018 scores are lower in the “Space and Place” and “Environment and Society” content areas compared to 2014; students also scored lower in “Environment and Society” compared to all previous assessments in 2014, 2010, 2001, and 1994.

Whenever NAEP Report Cards signal setbacks in student achievement, it is common to see an uptick of press lamenting the latest round of bad news about how much young people don’t know. Yet this media coverage does not convey the many opportunities NAEP assessments offer to stakeholders to gain valuable perspective on the educational context in which students, teachers, and schools pursue knowledge and instruction about our world. Geographers owe it to our discipline to dig deeper into these data to learn how geography education is or is not working for American students—and which students are missing out the most. Investing in this type of research now can not only influence the educational outcome for the next generation of geographers, it can also afford important insight into the practice and advancement of our discipline.

A Rich Source of Data for Research, Public Advocacy, and Equity in Education

NAEP reports do not include interpretations or explanations of achievement scores for different groups, nor do they make value judgments on the significance of the subject matter assessed. It’s up to education researchers to search for those clues in the data, and therein lies an important opportunity for geographers: to use NAEP data and reports in ways that support the discipline. Here are just a few examples.

Improve public understanding and perceptions of geography.

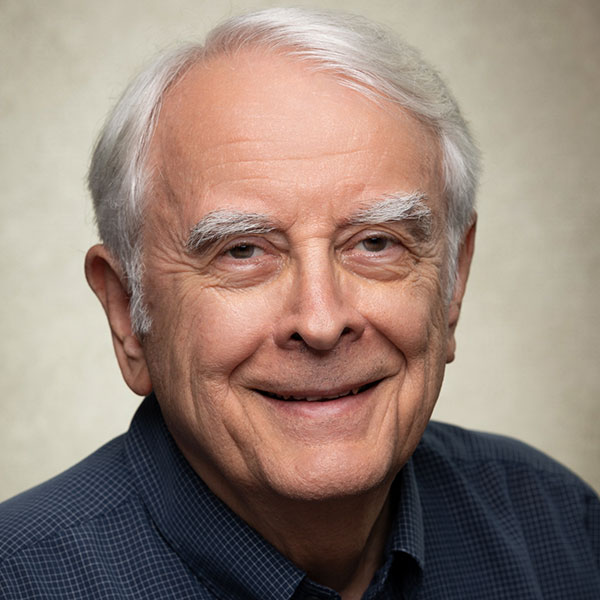

Geographers can use NAEP to counter misconceptions about what geography education entails by showing what it means to be proficient in geography. NAEP releases sample test questions to help the public understand how knowledge, understanding, and application in each content area are measured. Figure 1 shows a released “Spatial Dynamics & Connections” question that only 8 percent of eighth graders correctly answered. This is an opportunity for geographers to make a case for geography education by explaining how geography teaches conceptual knowledge and offers tools that can help young people understand and act on important and complex real-world issues such as urban growth and urbanization.

Address issues of equity, access, and justice in education.

Since the first geography assessment in 1994, NAEP has repeatedly reported stark achievement gaps. When achievement scores are examined by race and ethnicity, we see that scores for Hispanic and Black students have consistently fallen near “NAEP Basic” (defined as partial mastery of prerequisite knowledge and skills that are fundamental for proficient work). Over the same quarter century, disciplinary data show that geography college majors and professionals have remained disproportionately white and male.

Geographers have a robust record of analyzing relationships among race, ethnicity, and place, and there have been many national initiatives to enhance disciplinary diversity. NAEP offers geographers a chance to extend these efforts by conducting K-12 educational research utilizing NAEP’s deep contextual datasets to identify factors that appear to explain achievement gaps. This information could then be used to inform educational interventions that address achievement disparities.

Additionally, geographers can use NAEP data to search for clues about subject matter and instructional strategies that students of color perceive to be interesting, useful, and culturally relevant. All of this can open up new frontiers of research collaborations involving teams of geographers, psychometricians, educational assessment experts, and curriculum theorists.

Promote the values and uses of geography

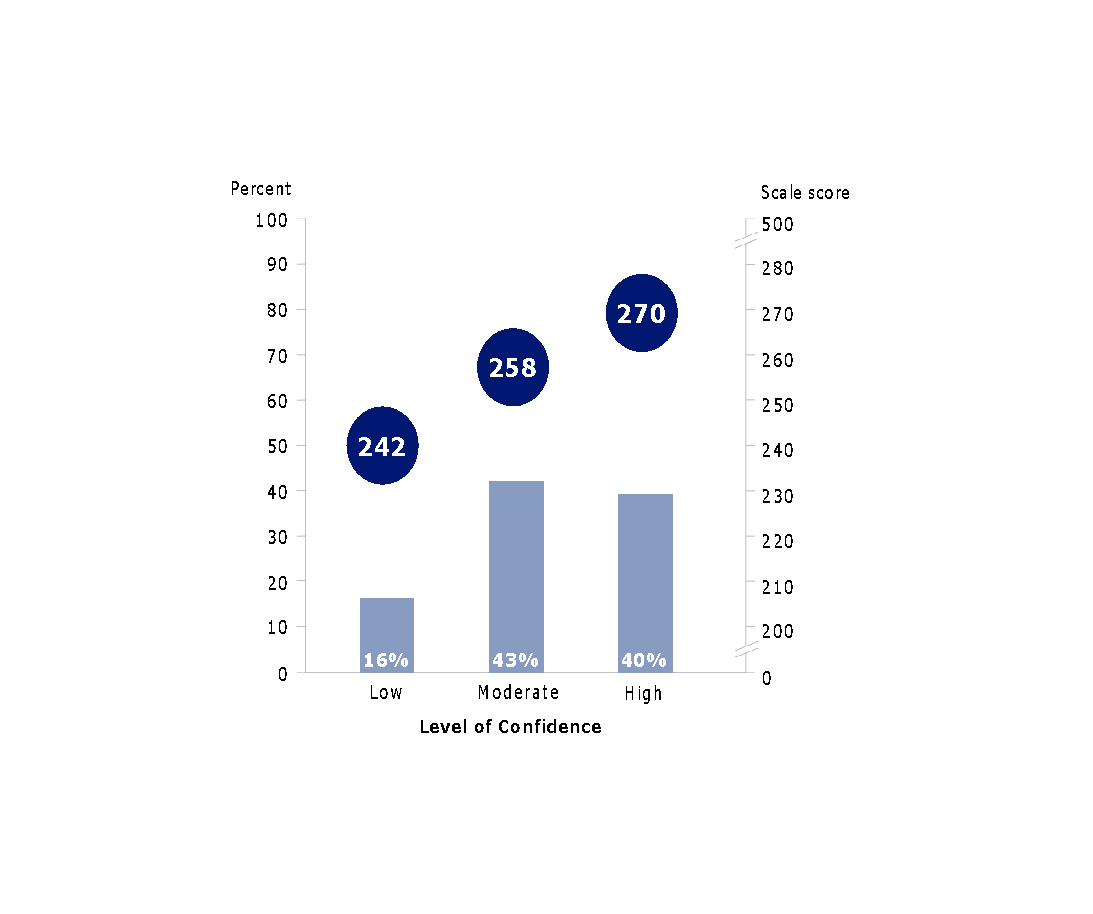

An important finding from diving deeper into NAEP data is that more confident learners perform better on the geography assessment (see Figure 2). How do we make learners more confident, you ask? Research using data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)1 suggests one of the most effective ways of increasing students’ confidence to do science is by conveying the applications and relevance of science.

Each of us, being geographers, are well-positioned to act on this information. For example, you can participate in AAG’s GeoMentors program, visit schools to discuss career opportunities in geography, share examples of how geographers apply their expertise in the context of work and civic life, and contribute to teacher professional development and curriculum initiatives.

AAG encourages our members to review the 2018 NAEP geography report and use the findings to renew efforts to improve the quality of geography education in the nation’s schools. A great tool for getting started is the NAEP Data Explorer.

The National Center for Research in Geography Education is also organizing a research network for geographers interested in pursuing research using NAEP data. The goal of this network is to plan a long-term research strategy utilizing NAEP geography reports and datasets. This is an opportunity for geographers to apply spatial methods for analyzing large quantitative datasets, potentially resulting in new geographic insights about education. AAG invites interested individuals to join this network by completing this form.

- Sheldrake, R., Mujtaba, T., & Reiss, M. (2017) Science teaching and students’ attitudes and aspirations: The importance of conveying the applications and relevance of science. International Journal of Educational Research, 85, 167-183.

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0073