The Invisible and The Silent

I am the parent of an adult child with intellectual and developmental disabilities and have spent the past two decades watching how society (dis)engages with him. People avert their eyes. People pretend not to see him. People give him a wide berth in store aisles.

I am the parent of an adult child with intellectual and developmental disabilities and have spent the past two decades watching how society (dis)engages with him. People avert their eyes. People pretend not to see him. People give him a wide berth in store aisles.

Some adults demonstrate shockingly bad behavior when he makes his noises or rocks back-and-forth. They display disapproval of his imperfect body and social conduct with facial expressions, comments, or gestures—such as picking up their groceries and moving to another checkout line. My reaction is a swift but reasonably (I think) calm tongue-lashing. Then, I always tell myself I won’t make a public display again. But I do.

Believe it or not, I’m happy when kids stare. At least they’re acknowledging his presence. And Jeffrey loves social interaction, if given the chance.

That Jeffrey is singled out like this reflects how our society is obsessed with physical perfection. Examples are too numerous to list. Vanity sizing is just one example. Is that international? If not, I’ll explain. In America, as bodies get larger, sizing gets smaller. A women’s size 6 today was a size 12 fifty years ago. Because…we cannot have socially defined “imperfections” in our bodies. So, the fashion industry wisely adjusts their sizing over the years. It is remarkable how I have been a size 6 my entire adult life (I hope you hear the sarcasm regarding myself).

Society trains us to have low tolerance of imperfections in our own and others’ bodies. It’s no wonder that in the race to perfection, those with physical imperfections are ultra marginalized by society. And if we are intolerant of weight gain or imperfect eyebrows, imagine how intolerant we are with non-functioning eyes or legs. We have been taught to actively ignore those imperfections and the bodies they’re attached to. Even being near such a person in a grocery line is unendurable. The only distance at which this imperfection can be tolerated is so far away as to be indiscernible. It is the spatial scale of exclusion.

And that’s when it happens. People with disabilities become invisible. Through able-ism, they are silenced, left alone past the detectable edges of the universe that able-bodies and able-minded individuals inhabit.

Fortunately, an increasing number of countries have laws that protect the invisible and silent. In the United States, for example, organizations are required by law to make reasonable accommodations for people with disabilities.

Of course, “reasonable” is vague and open to opinion. For example, under the cover of “reasonable,” the state of Alabama developed their ventilator rationing policy, which said: “Persons with severe or profound mental retardation, moderate to severe dementia, or catastrophic neurological complications such as persistent vegetative state are unlikely candidates for ventilator support.”

Horrible, right? Let us not cast our righteous stones. Alabama was not alone in developing policies for ventilator support that excluded people with imperfections. Fortunately, disability advocacy groups and the U.S. Health and Human Services Department have now ensured that ventilator policies don’t discriminate based on imperfection.

The American Association of Geographers is not immune; historically, it has not been welcoming of people with disabilities. At the same time, we have mostly not been overtly discriminatory. There is no need for intervention by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. But we have created a culture and a structure that presents barriers to inclusion and participation of people with disabilities. For example:

- Cost of our annual meeting remains a persistent (and often vocal) concern for many AAG members. AAG responds to this concern and attempts to defray costs when possible. Some strategies include: booking venues off-season, booking older venues, and including multiple locations in a single meeting. All of these strategies address membership demands to keep costs down. But, the result is an increase in barriers to participation for people with disabilities. Remember Denver 2005? Or Las Vegas 2009? Even without disabilities, it’s pretty hard to get around in a blizzard or between venues that are over 1km apart. How many times have you experienced overcrowded stairwells between sessions because the elevators were unable to support capacity? These are trade-offs that most membership welcomes in AAG’s responsive efforts to defray conference fees.

- The AAG website is a disaster and does not come close to providing Universal Access. It’s not even screen-reader compliant. We are unique in our antiquatedness relative to most other large, professional organizations. This is ethically unacceptable and, for an organization that is always worried about recruiting more people to Geography, it’s not even good business.

- The physical headquarters of AAG is Meridian Place. It’s far from being ADA compliant. People who use manual or motorized wheelchairs cannot enter the front door.

Why is this the current state of AAG? Historically, our collective membership has relegated issues of accessibility to the margins in favor of other priorities, such as saving money.

Fortunately, many accessibility issues are now being addressed by our new Executive Director, Gary Langham, and the AAG staff. For example, for the first time in my over 25 years in attending AAG meetings, child care for older children with disabilities was offered for the Denver 2020 meeting. Unfortunately, because of Covid, no one attended that meeting in person. But, the precedent was set. Don’t underestimate how big of a game-changer this support is for parents of older children with disabilities. For me, traveling as a parent of an older child with intellectual and developmental disabilities frequently represents an impossible obstacle. I’ve missed AAG meetings over the years because I couldn’t find support at home and because my son was too old for the child care provided by AAG.

As for examples two and three, though no concrete designs are yet in place, both website and Meridian Place renovations are actively being planned. ADA compliance and Universal Access are major parts of the discussion.

I am also delighted to announce that the AAG Council has unanimously supported the formation of a new AAG Accessibility Task Force. The members will identify the most pressing barriers to access within the AAG and develop strategies and guidelines to inform website design, building renovation, conference venue choices, and practices at conferences that enhance access.

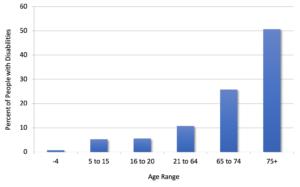

I will always argue that supporting access for even one person with disability justifies great effort. However, if numbers are important to justifying the effort, we should consider why persons with disability are such a small proportion of AAG membership and conference attendance. For example, each year prior to the annual conference, AAG asks members for accommodation requests. Few requests are made. But, according to the Institute on Disability, the overall rate of people with disabilities (in the U.S.) is almost 13%. Disaggregated, disability increases dramatically by age. The most common disability reported is ambulatory.

But, AAG does not receive accommodation requests from 13 percent of the attendees (i.e. equivalent to disability prevalence in the overall population). Perhaps the disability rate for geographers is shockingly low? I doubt it.

July 26 was Disability Independence Day, commemorating the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act that was signed on the same day in 1990. Yet, this day seemed to come and go with little notice. How many people did you hear talking about it, marching about it, let alone celebrating it? As we experience the wave of social justice demanding amplification of marginalized voices, an important perspective is missing.

For too long AAG members with disabilities have been kept invisible and silent. Based on my brief tenure as Vice President and President, I have learned that many such individuals left the organization or stopped coming to conferences when barriers become too overwhelming. The Accessibility Task Force will advocate for AAG members with former and current disabilities, as well as that large portion of us who will, based purely on statistics, develop future disabilities. If we wish to have true lifetime members, we need to get ready now.

The task force’s charge over the next two years is to identify barriers and develop remediation recommendations, to move beyond the ADA and what is required by law to create true opportunities for access and inclusion for people with disabilities. We’re at the start of new AAG leadership and experiencing a nationwide awakening to the damages of exclusion and social injustice. Yes, there is much work to be done. But as we enter the dawn of the new decade, I am profoundly optimistic that this dawn will cast a bright light that makes us see those with disability and the barriers that prevent them from being in the AAG, the discipline of geography, and our society at large.

This is when the invisible become visible.

And that is when we as individuals and the AAG become true facilitators to access.

— Amy Lobben

AAG President

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0077