New Orleans, Unmonumentalized

Much has been said and written about the recent removal of four New Orleanian monuments to Confederate leaders and an 1874 white supremacist uprising[1] [2]. More will be said at the Annual Meeting. The wide-ranging struggle over New Orleanian monuments includes how those memorials (re)defined New Orleans’ place in American space and time around Lost Cause ideology, variously comforting, threatening, affirming and negating certain historical/geographical narratives about the city, the American South, and the United States as a whole. They rendered the Confederate cause noble, the South distinctive yet within an American nationalist imaginary of post-bellum reconciliation and “redemption,” and simultaneously championed white supremacy while obscuring and/or glorifying the violence necessary to secure and maintain it. [3]

What New Orleans’ Confederate monument boosters wanted to do to and through monumentalized public spaces is important, as are the efforts of Take ‘Em Down NOLA to redefine those spaces, this city, and the American national story through monument removal. Geographers have written about the broader questions of historical memory and memorialization in the American South[4]. In considering the meaning-making done by and against Confederate monuments in the Crescent City, we should not forget what unmonumentalized places, events, and people do to historical memory, what I call the political geography of forgetting inconvenient history in New Orleans. What historical events unheralded in public spaces do to collective memory and the political definition of place can be as important as those monumentalized. Think of those numerous small plaques, sidewalk markers, and “stumbling stones” in Paris, Berlin, and other European cities to the deported and murdered in the Holocaust; Before their installation, the fact of Nazi extermination of Jewish life was largely invisible in contemporary urban landscapes, or confined to museums and monuments instead of distributed through quotidian spaces where those absent lives were lived and ended. Think also of how few, and recent, are Parisian memorials to Algerians killed in that city during France’s dirty war against Algerian independence. The relative visibility of memorializations of German (and Vichy French) state violence against Jews and the Resistance in the 1940s and near-invisibility in public space of French state violence against Algerians and Leftists in the 1950s and ‘60s both reflects and reinforces France’s belated historical reckoning with collaboration in World War Two and ongoing historical amnesia of crimes by “good” Republican, Gaullist France twenty years later.

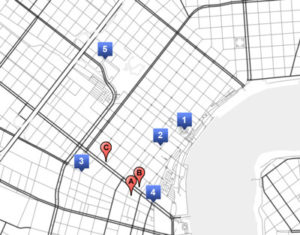

New Orleans’ passage through black slavery and slave resistance, the American Civil War, and Reconstruction and its counter-revolutionary rollback are the historical backdrop upon which Confederate monumentalization rested. Here, I wish to address a few historical sites within an easy walk from the AAG Annual Meeting that have remained unmemorialized, which are foundational to not just this city’s past and its reality today, but are constitutive of major aspects of America’s present reality. Check them out while you’re visiting New Orleans for the Annual Meeting. And if you do, consider what it means for our past, our present and our future these places aren’t part of the stories we tell ourselves about where we came from and how that shapes the prefigurative politics of who we are and can imagine ourselves becoming.

Start in Jackson Square at the heart of the French Quarter. During the Spanish colonial period, this was the Plaza de Armas at the foot of the seat of the colonial government and Catholic cathedral. As a slave society initiated by French colonists in 1719 and expanded by the Spanish, Louisiana was home to maroon communities of African people who emancipated themselves from bondage by retreating into wetlands behind the high ground near the Mississippi River from which plantations were cut out of the forests and cane brakes of South Louisiana. One of those people history has recorded was Jean Saint Malo, who led a community of Maroons east of New Orleans in present-day Saint Bernard Parish before his capture by Spanish slave-catchers in 1784. He was executed in today’s Jackson Square on June 19, 1784. There’s no historical marker of this event, or St. Malo’s life, in the Square. The hugely important role of African people in building colonial New Orleans and making a Revolutionary Atlantic, from the Louisiana maroons, the Haitian Revolution forcing France to sell Louisiana to the United States, the Haitian refugees who came to New Orleans in the 1790s and greatly shaped the city, to the Haitian-inspired 1811 slave uprising in St. John the Baptist parish not far from the city, are largely a constitutive absence in New Orleans’ public memory.[5]From Jackson Square, head down Chartres Street (it’s pronounced ‘Charters’ by locals) two blocks to the Omni Hotel on the corner of St. Louis and Chartres. This hotel sits on the former location of the St. Louis Exchange Hotel[6], built in the 1830s and the site of the most prominent slave market in the city, a city which in the 1850s had at least 50 different businesses buying and selling enslaved people. Five different slave auctioneers, buyers, and holding pens were located on this street corner alone; another cluster was around Esplanade and Decatur on the other side of the Quarter, a third in the modern CBD just west of Canal Street along Baronne Street. In a very material way, these innocuous New Orleans intersections were the beating heart, the nerve center, the financial nexus of that enormous engine of human suffering, forced migration, and economic valorization we call the American domestic slave trade. And it was that trade that pushed black slavery, Native American land dispossession, and the pernicious circuit of slave/land/cash crop accumulation westward through the South. The domestic trade centered upon New Orleans revived, through that territorial expansion, what might have been a stagnant institution, augmenting the tremendous political and economic power of the Slave South the United States of America, and later the Confederate States of America, fought so hard to sustain, expand, and defend from any challenge. And while the Louisiana State Museum in Baton Rouge now has a permanent exhibit on the New Orleans’ role in the slave trade, and the Historic New Orleans Collection put on an important exhibition on the city in the domestic slave trade in 2015[7], consider what it says not about New Orleans’, but about America’s, blindness to its history there exists today but one humble brass plaque acknowledging any of this in those New Orleanian neighborhoods through which so many thousands of enslaved people were bought and sold, through which the destiny of 19th Century North America was cast, making first the Mexican-American War and later the American Civil War inevitable.

In the St. Louis, people were auctioned under a grand dome in an auditorium ringed with decorative columns. In this city where slave markets and holding pens were ubiquitous, only two historical markers exist; in Algiers, across the river from the French Quarter, a marker attests to the landing site where thousands of enslaved people arrived from the Middle Passage. Across the street from the Omni is a marker on The Original Pierre Maspero’s Restaurant (440 Chartres) acknowledging that building was once the site of a slave auction. One architectural detail on Chartres hints at the former occupant of that block, part of the word ‘[EX]CHANGE’ preserved on an arch of the former St. Louis Exchange that was incorporated into the Omni, built on the site in 1960. It’s a poignant reminder of what this place was and how the materiality of New Orleans’ central role in the domestic slave trade survives in spite of the erasure of this memory from the city’s sidewalks and buildings.

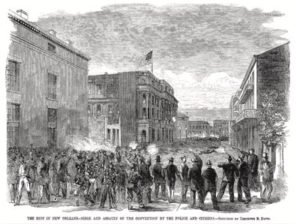

Keep walking down Chartres to Canal Street and turn right. Go up Canal four blocks and cross Canal to Roosevelt Way, then one more block to the corner of O’Keefe and Common. At this location a year after the end of the Civil War, on July 30, 1866, a meeting was held in the de facto State Capitol, the New Orleans Mechanic’s Institute, to amend the 1864 Louisiana Constitution, which did not guarantee equal voting rights to all men over 21, to include universal male suffrage. While slavery had been abolished through the 13th Amendment the year prior, black voting rights and civil rights more generally were flagrantly suppressed throughout the South, including Louisiana. The state’s Republican legislators and freedmen, many Union Army veterans, wanted to put into the state Constitution what would eventually become the 15th Amendment. That late July afternoon in 1866, around 1:30pm, a pro-voting rights march of black army veterans and others, marching from the Treme neighborhood just north of the French Quarter to the Mechanic’s Institute was met at O’Keefe and Common by an armed crowd of ex-Confederates and off-duty New Orleans Police and Firemen who attacked the march and subsequently the convention delegates inside the Capitol; at least 37 people were killed and more than 100 injured on this street and in the building, long since demolished.[8]

The 1866 New Orleans Massacre wasn’t just a local story; outrage over the killings nationwide was one of the precipitating events in the impeachment of Andrew Johnson, the Republican sweep of Congress in 1866 and 1868, the implementation of Military Reconstruction in the South and the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution. And yet, there’s no public memorialization of where it happened in New Orleans. Why is that? And what does it do to how Americans think about how their country came to be what it is today, or how New Orleanians imagine their city in American history, that it remains unacknowledged in public space?

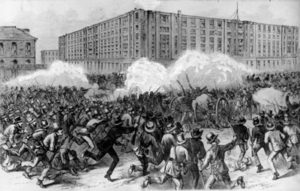

Head back to Canal Street, towards the river and the conference hotels for the Annual Meeting. Right where you’ll be crossing Canal Street many times with your fellow tote-bag toting AAG’ers between the Marriott and the Sheraton, this was a battlefield in an uprising against the United States on September 14, 1874. And the rebels won that day. Here along Canal Street down to Decatur near the river front, the Battle of Liberty Place saw the White League, a white supremacist paramilitary insurgency who sought to overthrow the Reconstruction state government of Louisiana, attack, defeat, and besiege the New Orleans Metropolitan Police, the State Militia, and the city and state government. Three dozen people were shot and killed in the battle. One block down from the Marriott at the Customs House, now the Audubon Butterfly Garden and Insectarium (423 Canal Street), Louisiana’s Governor, Republican loyalists, and U.S. Army troops were besieged for three days by 5,000 White Leaguers before military reinforcements arrived.[9] Even though Reconstruction in Louisiana survived until 1877, Liberty Place and many other related episodes of anti-Reconstruction violence around Louisiana and across the region between 1873 and 1876 affected a counter-revolution in the American South, known by its participants as “Redemption.” This counter-revolution ended black voting and civil rights, removed black elected officials from office, and cancelled the limited economic and public educational reforms that were attempted during Reconstruction.[10]

New Orleans was, again, central to these processes. The two 1870s U.S. Supreme Court cases that gutted the 14th Amendment’s civil rights protections for nearly a century implicated this city. The Slaughterhouse cases[11] (1873) – ostensibly about New Orleans’ municipal government power to regulate water pollution from dumping offal from abattoirs upriver from the city’s drinking water intakes – were hijacked into a broad constitutional judgment voiding federal power to enforce citizens’ civil rights violated by state governments. A short drive from the conference to the corner of Harmony Street and Tchoupitoulas (it’s pronounced CHOP-it-TOOL-us) takes you to as close as you can get to that former river batture dumping site, now occupied by the Port of New Orleans. And you guessed it, there’s no public memorial or signage or acknowledgment of this place’s historic role in undermining the enforcement of the 14th Amendment until the mid-1960s.

The case U.S. v. Cruikshank (1876), tried in New Orleans district court before heading to Washington, destroyed the last vestige of federal enforcement power against constitutional civil rights violations.[12] Cruikshank was among the few indicted by federal agents for the infamous April 13, 1873 Colfax Massacre, in which more than 100 African-Americans were slaughtered at the Grant Parish courthouse by a white mob in the course of overthrowing the local, pro-Reconstruction, government.[13] (In that tiny North Louisiana town of Colfax, the official State of Louisiana historical marker emplaced in 1950 reads – today, in 2018 – the “Colfax Riot” … “marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.” A private memorial, dating to 1921, in that town’s graveyard to the three white rioters who died in the violence acknowledges they fell “fighting for white supremacy.” Following his initial trial in New Orleans, Cruikshank was acquitted by the U.S. Supreme Court who ruled the federal government overstepped its powers to enforce federal constitutional guarantees violated by state and local governments. This confirmed black people could be massacred with impunity and the national government would not intervene to hold them criminally responsible.

New Orleans did not fail to memorialize the Battle of Liberty Place. The problem is the city, soon after the insurrection, decided to honor and glorify the insurgents with a stone obelisk erected on Canal Street in 1891, relocated a short distance in 1993, and finally removed in 2017. This column is not about whether that monument or others in New Orleans should have been removed, but I do note that today there’s nothing in the area that tells the story of what really happened there in 1874, how it led directly to the imposition of Jim Crow segregation, impunity for anti-black violence, and disenfranchisement for 90 years, or what America would be like if history had gone another way, if equal voting rights had been enforced, if Reconstruction had not been subverted and different people with a different agenda had served in that pivotal Southern Congressional bloc in the following century. My opinion is we’d have had the legislation passed in the New Deal and Great Society about 50 years sooner, and a very different regional and racial distribution of wealth and power in this country. To not teach the historical/geographical hinge a site like the Battle of Liberty Place pivots between diverging paths in the making of America, the one taken that led us to this moment and another forsaken, is to rob us of our collective imagination to make a different future. In that sense, it’s not enough to just take down the monument.[14]

A last stop, assuming your feet don’t hurt too much already, is back up Canal Street, once more past the throngs of geographers, all the way to Rampart Street at the northern boundary of the Quarter. Turn right and follow Rampart to Armstrong Park, just past Congo Square, and go through the main, archway entrance opposite St. Ann Street. Inside the park, near where the Mahalia Jackson Theatre for the Performing Arts now stands, was the old Orleans Parish Prison. At this location the lynching of 11 Italian immigrants took place on March 14, 1891, an event that resonated widely to catalyze nativist, anti-immigrant sentiment in American public opinion.[15] The New Orleans of the 1880s and 1890s attracted thousands of Italian immigrants, many of them Sicilians, who worked on the docks, ran small shops, and did truck farming.[a] So many Sicilians crowded into the French Quarter, back then a decaying slum, that it earned the nickname ‘Little Palermo.’ When in October 1890 the New Orleans Police Chief was shot dead by unknown assailants, the Mayor and Police decided the guilty were Sicilians and rounded up 19 men for trial. Nine were actually tried and were acquitted of all charges. The next day a huge crowd, led by prominent New Orleanian legal and political figures, was agitated to action and led to the prison where they forced entry to the building and killed eleven of the 19 Italians held inside, eight managing to hide. The grand jury empaneled to investigate the murders made no indictments, even agreeing in writing with the lynch mob’s charge the jury had been bribed to acquit the Italians, so no one was held accountable.

National press coverage of the police chief’s murder, the trial, and lynching was extensive. Leading American newspapers like the Boston Globe and New York Times editorialized in favor of the lynching, while the Italian government and Italian-Americans widely decried the violence and lack of punishment for the murderers. Through these sensational press stories, Americans were acquainted for the first time with terms like “Mafia,” “stiletto,” and “vendetta” in service of the criminalization/racialization of southern Italians as undesirable persons to be discouraged or barred from the United States. So while mass immigration by southern and eastern Europeans to America would continue for another three decades, the 1891 New Orleans Italian lynchings were a critical, foundational moment normalizing hostility against these new immigrants[16], building towards the National Origins immigrant quota system that heavily restricted south and east European migration, and all but eliminated immigration from Africa or Asia, from 1924-65. We should all know about this, every child should learn it in American history class. In a New Orleans so proud of its Italian/Sicilian heritage — its St. Joseph’s altars, the Monument to the Immigrant showing an Italian family, knapsack and kerchiefs and caps and chubby baby and all, arriving from the river in Woldenberg Park with an angel harkening behind them to the Old Country, Irish and Italian parades on St. Patrick’s Day (don’t ask, it’s too complicated) – it’s inconceivable to me this event in this city is unmarked, unmemorialized, invisible in the middle of a public park. Because the events of 1891 silently shout every time a sitting Cabinet member praises America’s 1924 restrictionist immigration law[17]. And we don’t hear. And we could use those memories these days.

There’s numerous self-guided tours on the internet you can use to experientially learn more critical New Orleans history (and geography). I like the excellent collection of tours online at New Orleans Historical. And you can hire a tour guide to tell and show you more than I’ve done here; Hidden History Tours does excellent walking and bus tours of African-American New Orleans history from people who know the struggle to make this history visible because they’ve waged that struggle themselves. On the Annual Meeting agenda, consider the April 9th Black Geographies Past and Present field trip to Whitney Plantation, the daily 4/10, 4/11, 4/12 and 4/13 African Life in the French Quarter Walking Tours, the Thursday 4/12 A People’s Guide to New Orleans: Resistance in the Treme Walking Tour, or the Friday 4/13 Interpreting Slavery at River Road Plantations field trip. For those inside the meeting, consider hearing the President’s Plenary and subsequent discussion by five panelists on 4/10, the themed sessions on black geographies like Mike Crutcher’s 4/11 address on the Treme neighborhood and the 4/14 session on Clyde Woods’ Development Drowned and Reborn. See you in New Orleans.

— Brian Marks, Louisiana State University and A&M College

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0031

[a] In my family’s story, one of my great-great grandparents was a Sicilian immigrant who stowed away on a ship bound for New Orleans, then jumped into the Mississippi and swam ashore just below New Orleans to arrive clandestinely.

[1] Jennifer Speights-Binet and Rebecca Sheehan, “Confederate Monument Controversy in New Orleans,” AAG Newsletter, January 2018. https://news.aag.org/2018/01/confederate-monument-controversy-in-new-orleans/

[2] Mitch Landrieu, 2018. In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History. New York: Viking.

[3] Gaines Foster, “How the South Recast Defeat as Victory with an Army of Stone Soldiers,” Zocalo Public Square, September 28, 2017. https://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/2017/09/28/south-recast-defeat-victory-army-stone-soldiers/chronicles/who-we-were/

[4] Owen Dwyer and Derek Alderman, eds. 2008. Civil Rights Memorials and the Geography of Memory. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

[5] Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, 1992. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

[6] Richard Campanella, “The St. Louis and the St. Charles: New Orleans’ Legacy of Showcase Exchange Hotels.” Preservation in Print, April 2015. https://www.richcampanella.com/assets/pdf/article_Campanella_Preservation-in-Print_2015_April_St%20Louis%20and%20St%20Charles%20Hotels.pdf

[7] John Pope, “Slavery in New Orleans is the subject of a harrowing exhibit at the Historic New Orleans Collection.” New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 27, 2015.

https://www.nola.com/arts/index.ssf/2015/03/slavery_in_new_orleans_is_the.html

Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “Sighting the Sites of the New Orleans Slave Trade.” WWNO New Orleans Public Radio, November 5, 2015.

https://wwno.org/post/sighting-sites-new-orleans-slave-trade

[8] James Hollandsworth, 2004. An Absolute Massacre: The New Orleans Race Riot of July 30, 1866. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

[9] Lawrence Powell, 2013. “Reinventing Tradition: Liberty Place, Historical Memory, and Silk-Stocking Vigilantism in New Orleans Politics.” In Sylvia Frey and Betty Wood, eds. From Slavery to Emancipation in the Atlantic World. London: Routledge. pp. 127-49.

[10] Nicholas Lemann, 2006. Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War. New York: Macmillan.

[11] C-SPAN, 2017. Landmark cases: The Slaughterhouse Cases. https://landmarkcases.c-span.org/Case/3/The-Slaughterhouse-Cases

[12] Robert Goldman, 2001. Reconstruction and Black Suffrage: Losing the vote in Reese and Cruikshank. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

[13] LeeAnna Keith, 2008. The Colfax Massacre. New York: Oxford University Press.

[14] Scott Marler, “Removing the Confederate Monuments In New Orleans Was Only a First Step Toward Righting the Wrongs of History.” The Nation, June 14, 2017.

[15] Alan Gauthreaux, 2010. “An Inhospitable Land: Anti-Italian Sentiment and Violence in Louisiana, 1891-1924. Louisiana History 51(1): 41-68.

[16] Christopher Woolf, “A brief history of America’s hostility to a previous generation of Mediterranean migrants – Italians.” Public Radio International, November 26, 2015.

[17] Adam Serwer, “Jeff Sessions’s Unqualified Praise for a 1924 Immigration Law.” The Nation, January 10, 2017.