Daydreams and Nightmares in the Northern Forest: A Quarter Century of Change

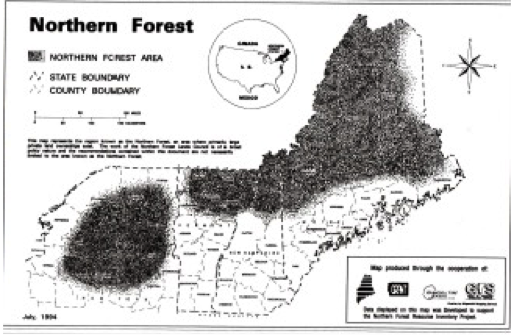

The Northern Forest is a term used by forest activists, policy wonks and some geographers to describe the forested regions of upstate New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. This is a region of scattered population, glaciated hills and valleys, many lakes and rivers, and several substantial mountain ranges (Irland, 1999; 2011). In its fall displays of color, the red and yellow maples and birches are studded by dark green pines and spruce. It is virtually the last redoubt of native brook trout populations; in a few coastal Maine streams tiny surviving runs of Atlantic salmon cling to life. This region was accustomed to long-standing private ownership by paper companies, well-established timber families, and Kingdom Owners– descendants of New York wealth from the 1890’s, with their lakes and “Adirondack Camps.” The region has an aura of remoteness and wilderness character, regularly burnished by writers and artists since Thoreau’s visits in the 1840’s and the glowing paintings of Hudson River School artists. Into countless households each year, the mail order catalogs of the LL Bean Company arrive, with covers displaying appealing images of wild solitude. They become the suburbanites’ mental picture of the Northwoods. Visitors were often stunned, then, to drive into the woods and see logging trucks, recent clearcuts, and for sale signs for wildland lots. Many wanted something done about it.

A regionwide outbreak of spruce budworm attacked spruce and fir stands from the early 70’s to the mid 80’s, leading to widely publicized spray programs and accelerated cutting in Maine where the effects were most serious. Recreationists could readily access the most remote corners of the Northwoods on gravel roads, following the end of log driving on the rivers.

This region was the culture hearth of the nation’s lumber, log driving, and paper industries; lobbyists and executives for these industries once carried big sticks in state capitals. By the late 1980’s, though, large private holdings were beginning to turn over to new owners, often non-industrial ones. Fears began to spread that the traditional model of timberland ownership would burst wide open leading to widespread shoddy subdividing and development, loss of public access, diminished timber supply, and then loss of jobs as mills could not meet their wood needs. In 1990, and again in 1994, major studies were done on these issues, funded by federal dollars.

By the early 1990s, it was thought that by judicious public policy, something resembling the traditionally stable Northern Forest landscape could be retained, fostering stable employment in rural areas and milltowns, widespread public access to private lands, and desirable wildlife habitat. In 1989, a regionwide study was launched, the Northern Forest Lands Study, to assess these issues with a guiding committee of state officials and stakeholders (USDA Forest Service and Governors’ Task Force, 1990). A followup in 2004 was a more ambitious effort to conduct detailed research and develop policy options (Northern Forest Lands Council, 1994; Northeastern State Foresters Association, 2005).

These projects conducted local public meetings to obtain input and encountered loud protests from local groups, especially in the Adirondacks, who – correctly — saw the reports as efforts to build support for more land protection. They saw this as threats to their economy and autonomy (Porter, Erickson, and Whalley, 2009). One result of this was that both reports, while depicting longterm issues and needs, had to tread gingerly by burning incense to the idols of local stakeholder input before any recommendations were made. In its 2004 Report, the Northern Forest Lands Council offered a saccharine vision of the future forest and the industries and communities depending on it. They recognized that this could not be achieved without improved public policies, for which they offered numerous suggestions. But they assumed a level of stability in markets and industry structure that was not to be.

Rarely has there been a more dynamic period in the region’s forest history than the 1990-2015 period —

Numerous small wood processing companies (Irland 2004) have been driven out of business by furniture imports from China.

From 2000 to 2015, newsprint usage nationally fell by 70%; printing and writing paper consumption by one third. The post 2005 housing crash cut national lumber production by half, and it has since barely recovered. Today, there is no paper being manufactured along Maine’s Penobscot River, and lumber manufacturing remains as a pale shadow of what once was. Primary paper mills have virtually vanished from New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire. In parts of the region, more wood is being burned to generate electricity than to make pulp or paper. Had anyone in 1990 predicted all these events they would have been dismissed as delusional. Domestic market crashes and surges in imports upset the hopes for a stable forest economy with prospering little milltowns stretching from Tug Hill to Eastern Maine

The 1990 study was prompted by concerns that industry would sell its land to others, who would have less reason to keep it in forest and retain public access customs. This concern proved all too well founded: for a host of reasons, forest industries sold off their holdings almost completely, and many of the mills as well (your present writer was among those who failed to predict this). At one time, with a stroll down “Paper Industry Row”, on E. 42d Street in New York, you could talk to the owners of much of the forest of the region, or at least their Wall Street bankers. No longer. Many of the longtime family holdings, such as the Adirondack “Kingdoms” held by heirs of the Robber Barons since the 1890s, went on the block as well. New owners represented a wide variety of interests, including newly rich billionaires, and investment funds managed for pension funds and institutions (Irland, Hagan, and Lutz, 2011). More than a little of this land found its way into conservation uses via NGO’s, public agencies, and conservation easements.

From some perspectives, progress has been made: counting fee ownership and conservation easements, 19% of Maine is now in conservation ownership. Important gaps in the Adirondack Park have been filled in. In many areas, however, the resource “took a haircut” in this process as smaller tracts and outholdings were sold off. Often the buyers were exploitive “liquidators” who stripped the timber and sold the land as “leisure lots” in sizes that would elude local land use controls (if there were any at all). Today, many who loved to hate the paper companies wistfully admit that wish we could go back to those times. Fortunately, the housing crash has cut deeply into demand for such lots, but signs of gentrification on large “view lots” are emerging once again, especially near ski areas. The old rustic “ski chalet”, often self-built, is being replaced by virtual mansions, with 2 car garages and mowed lawns. Development on view lots is eroding the sense of remoteness that once characterized much of this region, with implications for public access and wildlife habitat that are only beginning to be recognized.

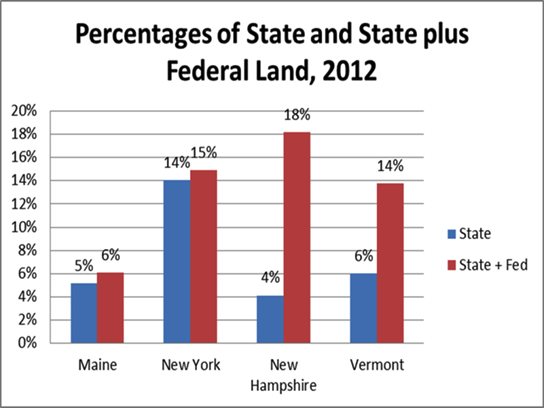

Political cultures regarding public land ownership and regulation vary from state to state across this region, despite its apparent ecological and economic similarities. Substate institutions have arisen in New York (Adirondack Park Authority), New Hampshire (unincorporated portions of Coos county), and Maine (Land Use Planning Commission for 10 million acres lacking any local government). A major influence has been concentrations of wealth and population in the Boston-New York coastal strip. The Northern Forest is the recreational and second home backdrop for these regions, and most of the conservation accomplishment has been lobbied from those urban areas. So the region has a distinct north-south political divide. Broadly speaking, advocates of the National Forests on Vermont and New Hampshire have allowed the 2 states to pass much of the cost and bureaucracy of administering dispersed forest recreation to federal taxpayers. In New York and Maine, by contrast, there is very little federal conservation land, while New York’s constitutional Forever Wild in the Adirondacks represents a huge state-managed stretch of wild land.

Both Maine and New York are not favorable to federal ownership, except where federal dollars will pick up costly coastal property (e.g. Acadia NP; Rachel Carson NWR; Fire Island National Seashore on Long Island … but these are not in the Northern Forest) One lesson has been that creating federal land units has been far easier than administering them. Drawing lines on maps cannot make the divisions among various publics go away. Since 1990, changes in fee ownership in the Northern Forest have not been substantial, amounting to only about 800,000 acres leaving private ownership over the quarter century. Most of the conservation achievement has been via conservation easements, which represent the removal of development rights from land remaining in private hands.

The entire region has been used to urban elites picking and choosing locations for National Parks and other major conservation units, perhaps to a degree unmatched elsewhere in the country. This yielded major conservation successes: the Adirondack Park, Acadia NP, the White Mountain National Forest, and Baxter State Park. Yet it exacerbates the north-south political divides noted above.

In Maine, since about 2010 an organized program of blowback against the programs favored by Northern Forest Lands advocates has been under way. A Republican governor and legislative allies have been blocking Maine’s premier land conservation program, attempting to roll back other conservation policies, and trying to pull the teeth from Maine’s Land Use Regulation Commission (newly renamed the Land Use Planning Commission and asked to work with more county input). This revolt may be narrowly based on a few discontented small businesses in rural areas, but it has had an impact. Leaders of the blowback have not, it seems, paid any political price for their actions. Conservation and environmental groups seem slow to realize the implications.

In 2016, the entomologists are telling us that the spruce budworm is coming back – and its ultimate spread and impacts are unpredictable (Maine Forest Service, 2016). This brings a further dark cloud to the horizon for private forest owners.

The Northern Forest’s history of land use change, the underlying forces, and the effectiveness – or lack thereof—of state and federal forest policies offer many important topics for study by geographers (Wallach, 1980). The literature of the field seems sparse in attention to this unusual region; perhaps the Boston meeting will stimulate more interest.

Lloyd C. Irland is a forestry consultant in Maine, a former forestry school instructor, and public official in Maine state government. He contributed land use analysis to the 1990 Northern Forest Lands study and is author of many papers on forest resources as well as 2 books on the northeast’s forests. lcirland [at] gmail [dot] com.

Author’s Note: The title of this article does homage to Daydreams and Nightmares, a 1971 book by my colleague W. R. Burch Jr, who was one of the earliest to apply sociological insights to forest resource and natural resource problems.

References

Burch, W. R. Jr. 1971. Daydreams and Nightmares: a sociological essay on the American Environment. New York: Harper and Row.

Foster, David R. et al. 2010. Wildlands & Woodlands: A Vision for the New England Landscape. Petersham: Harvard Forest. May. https://www.wildlandsandwoodlands.org/

Irland, Lloyd C. The Northeast’s Changing Forest. Harvard Forest, Petersham, MA (dist. By Harvard Univ. Press). 1999.

Irland, L. C., J. Hagan, and J. Lutz. 2011. Large timberland transactions in the Northern Forest 1980 – 2006. Yale Global Institute for Sustainable Forestry. Private Forests Working Paper No. 11. https://gisf.yale.edu/publications-presentations/gisf-research-reports

Irland. Lloyd C. 2004. Maine’s forest industry: from one era to another. In: R. E. Barringer (ed.) Changing Maine. Gardiner, Maine: Tilbury House, pp. 362-387.

Irland, Lloyd C. 2011. “New England Forests: Two Centuries of a Changing Landscape”

In, B. Harrison and R. Judd, eds. New England: A Landscape History. Cambridge: MIT Press. Pp. 53-70.

Maine Forest Service 2016. Spruce Budworm Internet Hub

Northern Forest Lands Council. 1994. Finding common ground: Conserving the Northern Forest. Recommendations of the Northern Forest Lands Council. Concord, NH.

Northeastern State Foresters Association.2005. Northern Forest Lands Council 10th Anniversary Forum. Concord. Northeastern State Foresters Association. www.nefainfo.org/uploads/2/7/4/5/27453461/nflcfr_final…

Porter, W. F., J. D. Erickson, and R. S. Whalley. 2009. The Great Experiment in Conservation: Voices from the Adirondack Park. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

USDA Forest Service and Governors’ Task Force. 1990. Northern Forest Lands Study. USDA Forest Service, Rutland, VT.

Wallach, Bret. 1980. “Logging in Maine’s Empty Quarter” Annals of the Association Geographers , vol. 70 (4):542-552. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1980.tb01331.x

Focus on Boston is an on-going series curated by the Local Arrangements Committee to provide insight on and understanding of the geographies of Boston and New England. The 2017 AAG Annual Meeting will be held April 5-9, 2017, in Boston.