Finding your Parachute or The PhD is Not Just for Academics

Graduate students are haunted by the specter of future job uncertainty. Many Master’s students wonder what they will do with their degree. For PhD students, the period between becoming ABD and completing the dissertation elicits a queasy feeling. What will the academic job market be like? Will I land a job in my specialization, will I get a visiting position somewhere, or will I miss out entirely, forced to eke out a living until the next year’s job ads come out? These fears are well founded; academic job commitments for doctoral recipients are under 50%.

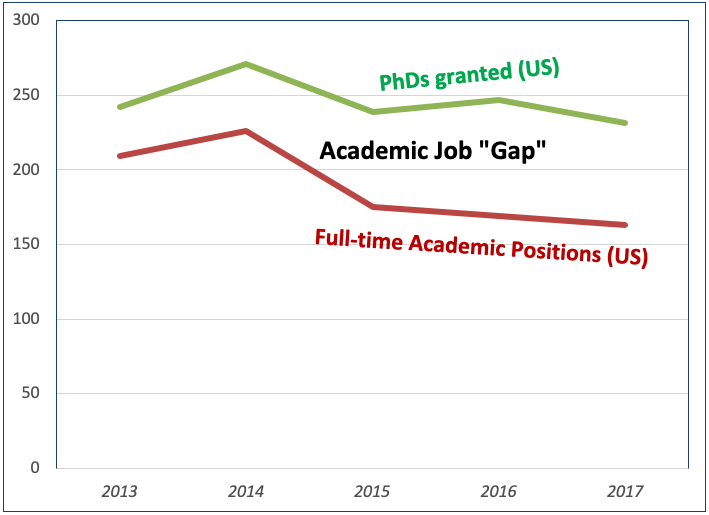

The picture is a bit better in geography. This chart compares the number of U.S.-based entry-level, full-time, permanent academic jobs posted on the AAG website with the number of completed doctorates for the last few years. That still leaves a pretty big deficit between eligible applicants and job availability and does not account for already employed professors on the hunt for something new.

While there will always be job anxiety, part of it stems from the idea that the PhD must inexorably lead to an academic, preferably tenure-track, position. To many, it carries the same connection as MD to physician or JD to attorney. A doctorate is training for academia, so the thinking goes, but not a whole lot else. Departmental culture can bolster this viewpoint as well, exalting those students who land an assistant professor position and ignoring all other job prospects. Graduate school is viewed as an apprenticeship to a singular vocation.

Yet we know that many PhDs do work in non-academic posts, and that such jobs can bring fulfillment, stimulation and financial stability. The NSF’s Survey of Doctoral Recipients shows that half or more of all recent PhD recipients work in business, government, or some other form of non-academic employment We need to say loud and clear that non-academic careers are just as valuable as academic careers. These jobs usually pay better and the level of job satisfaction can also be higher. A popular book on careers outside of academia (Basalla and Debelius 2015) uses anecdotal evidence to show how non-academic positions present interesting challenges, stimulating colleagues, and often less guilt and more accomplishment than their academic counterparts. My last three PhD students have gone on to rewarding careers in government, nonprofits, and business. Such jobs also bring geographical flexibility, allowing them to live with their partners, stay in a place they like, and not follow the holy academic grail across the country and the world.

Beyond this, the demand for the kinds of critical skills achieved by advanced geographers only continues to grow. A recent report by the World Economic Forum touting the “4th Industrial Revolution” forecasts greater demands for creativity and originality, critical thinking, systems analysis, technology programming, and the like. Geography not only gives students the human (creativity, critical thinking) and technical skills predicted to be more valuable—it synthesizes them. Past President Sarah Bednarz has described “Geography’s Secret Powers” as the thinking that harnesses spatial concepts, spatial representations, and reasoning as well as applies this knowledge to using various geospatial technologies. Geography Masters and PhD students come out of universities prepared with spatial and geospatial thinking—ready to take on the future of work.

Students wishing to pursue alt-academic professional opportunities have to change their job search strategies. Getting a tenure-track job is a bear, but it is relatively straightforward and transparent. You need only go to your friendly AAG Jobs in Geography, see the jobs that apply to you, and follow the directions. The types of materials needed—cover letter, CV, letters of recommendation, perhaps a couple of published articles—are also pretty standard.

There are many places to look for jobs outside the halls of ivy, but no single place to look. Positions may be widely advertised or may rely on personal information. Employers are unlikely to ask for a specialty in “global urbanism” or “biogeography” but be more inclined to seek a set of skills and experiences relevant to the job at hand. The emphasis is less on your prospects as a rising professor and more on how well you fit the organization. Companies or agencies may not care about your dissertation or your articles, and will request a 1–2 page resume instead of a multi-page CV. And while academic positions can bring in up to 100 applicants, jobs on the outside can see even more competition, requiring an even greater ability to stand out.

So how can our community facilitate these options? We advisors are remarkably good at instilling geographical skills in our students but not so good at showing them how to market these skills outside the world of colleges and universities. While for some academia is a second career, most of us marched straight into tenure-track jobs after earning our PhDs. University life is all we really know. My fluency in charting the trail to an assistant professor position falters when I try to prepare a student for something that deviates from this very narrow path. Moreover, students may feel anxious about telling advisors that they do not wish to pursue an academic career. This requires a certain degree of sympathy on the advisor’s part, a willingness to acquire knowledge, maybe even participating in and establishing PhD career fairs—in other words, a more sophisticated version of what we do to enhance job prospects for our undergrads.

The department or university can provide resources to their students. One such option is a subscription to Versatile PhD – a website providing examples of jobs, resumes, pep talks, and lots of other material. Some of this is free, but the paywall comes up fast. Developing a network of alumni who have successfully gone into worlds beyond academia could be a fantastic resource, and one that could allow for some early-stage mentoring and connection-building in a chosen field. Knowing somebody in the right place at the right time works. Bringing in geographers in these careers who can talk about them as part of a speaker series or some other event provides insights into potential opportunities.

And let’s not forget our Master’s students. While much of the angst is focused on the doctoral student in search of a job, graduate programs include many people who want to further their love of geography by getting a Master’s degree. Where I went to graduate school, there was an impression (at least I felt it) that the Master’s was just a way station to the doctorate. Some geography departments don’t even require a Master’s and encourage their students to go straight to the PhD. Yet we have far more MA, MS and now MGIS students than PhD students, and the majority do not want a PhD and the academic life. Focusing on this group and their career options after graduate school is a beneficial exercise as several of the strategies used to help them along can also apply to PhD students.

And finally, can the AAG do more? As an academic, one of the nicest aspects of the annual meeting is the opportunity to catch up with old friends. This especially includes former PhD students and MA students who did their PhDs elsewhere. But for geographers who did not go into academia, the incentives are often gone. They may not get money or time from their organization, they may feel like the overall vibe is far too “academic” and ignores their needs, and they may feel more and more cut off from their professor friends. I appreciate the specialty groups—notably the Business SG, Applied SG and the Public/Private Affinity Group—for promoting the non-academic world. But the fact remains that less than 11% of our members come from outside higher education. Data from McKinley showed that AAG members in the non-academic world were far less likely to attend the annual meeting, and those who did attended, did so less frequently. If we confine our appeal to only academic-bound geographers, we risk limiting the reach of the AAG and cramping the opportunities for current AAG members.

Geography is larger than just colleges and universities. The AAG should reflect the entire spectrum of geographic careers.

— Dave Kaplan

AAG President

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0062